Why digital presenteeism is a big problem in the workplace

Before the en-masse shift to remote work, sitting at your desk from 8 am until 5 pm was a proxy to indicate that you were working. If you wanted to really show your loyalty and effort toward the cause, you might have put in an extra 30 or 60 mins in the office (whether you worked or not was another thing).

What is presenteeism in the workplace?

Presenteeism is defined as the act of being present at work but not actually working. You’re doing the hours but the work has almost become performative – if you’re doing it all. In an extreme but comical example, Stanley Hudson, from the US ‘Office’ series has perfected the art of presenteeism and is completely oblivious to anything going on around him.

You might think this behavior would be a thing of the past, now that many workers are spending much more time working from home. But a new report from Qatalog and GitLab shows that presenteeism is still a problem and getting worse. Except in the new world, it’s gone digital.

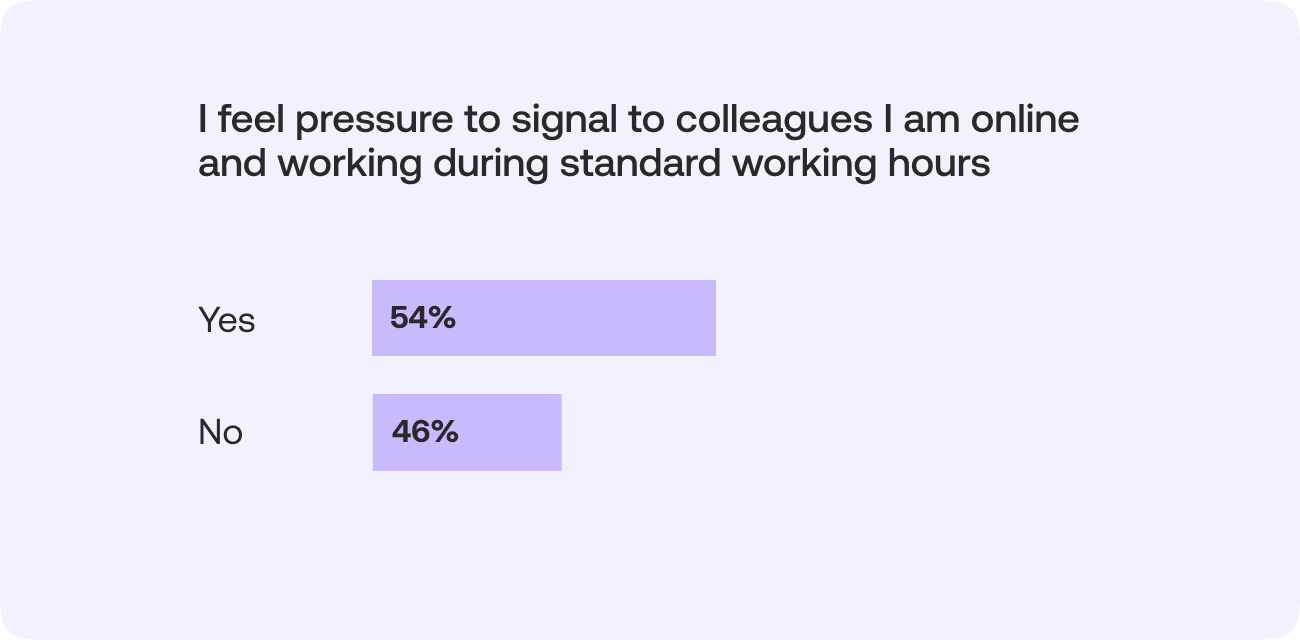

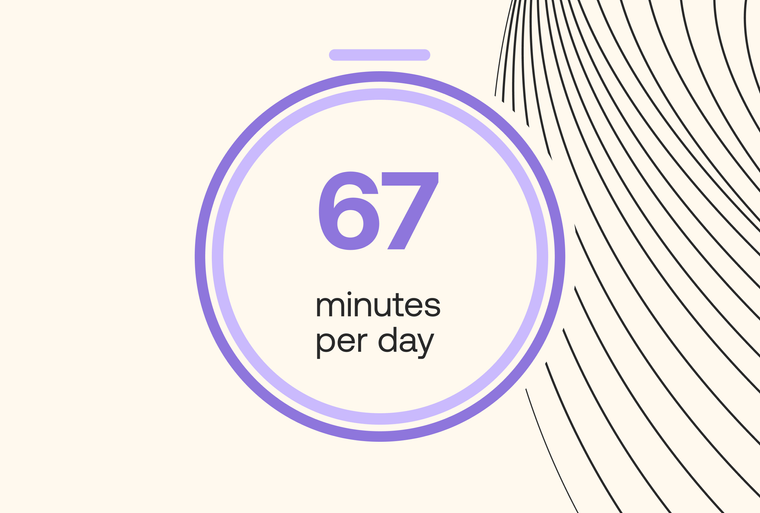

Over half of those polled (54%) said that they still feel pressure to be visibly online at certain times of the day. On average, this results in workers spending an extra 67 mins each day (5.5 hours a week!) online, in addition to normal working hours, as they attempt to avoid suspicion from colleagues and bosses that they are not working hard enough.

This kind of digital presenteeism manifests as keeping your Slack status set to online, or replying to Teams messages from your mobile device while preparing dinner. Reading and replying to emails during your favorite Netflix show might feel productive, but it is presenting and endorsing an always-on attitude to your colleagues.

Changing from an always-on culture is hard

At its core, digital presenteeism is a cultural issue. More than half of workers (54%) say their colleagues are stuck in old habits that make it hard to work asynchronously, while almost two-thirds of people (63%) believe that their managers prefer a ‘traditional culture with employees in the office.’

Organizations with this mindset, which prefer the traditional ‘bums-on-seats’ approach to monitoring productivity, are going to be difficult to change. They are typically led by those who worry that providing more flexibility and allowing employees to manage their own time means giving up too much control. Even if that control was always an illusion. In addition, if workers aren’t in the office, but they still feel like they’re being measured by how long they spend working, they’ll do the next best thing, which means appearing to be online wherever they can.

Effects of presenteeism in the workplace

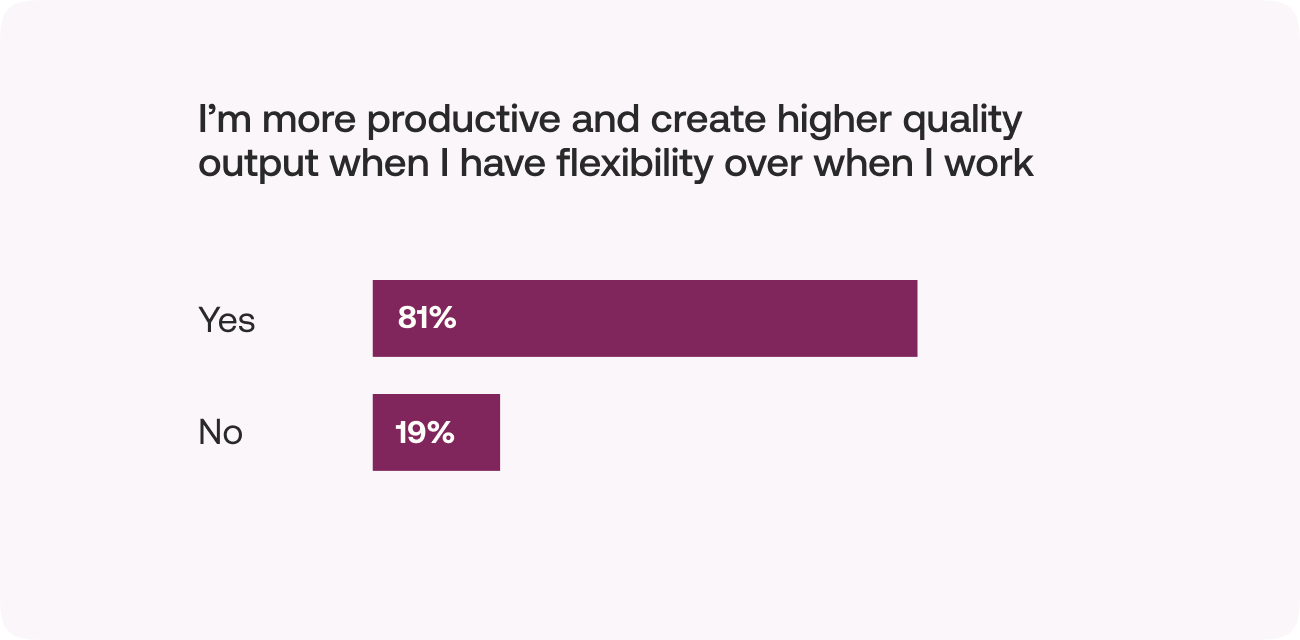

Some bosses will tell you that getting employees back in the office is good for business. The reality is that 81% of workers feel like they’re more productive, produce higher quality output, and are happier when they have flexibility over when they work. That’s why a culture that values time in front of a computer over the quality of output is fundamentally flawed.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. Everyone works differently, and we know that people are productive at different times. Of course, you can still fill your day with ‘stuff’, by ticking off tasks to make it look like you’re working, but is it really your best work? Our engagement and attention will often ebb and flow during the day and workers who recognize those patterns and have the freedom to adapt their day to accommodate for this will naturally be more productive, in the broadest sense of the word.

Equally, simply putting a whiteboard in a room full of people doesn’t mean they’re going to instantly spit out some great ideas. Creativity requires space and time to think, mull over and execute properly. You’ve probably had some of your best ideas in the shower, walking the dog, or sitting in the garden, and countless studies have shown this to be the case. But this is rarely compatible with a rigid 9-5 culture.

Does working asynchronously get rid of presenteeism pressures?

It should do, but you can’t do it alone. It needs to be organization-level change, as even those working async might still be worried that their work isn’t being recognized if the company isn’t set up properly for asynchronous work.

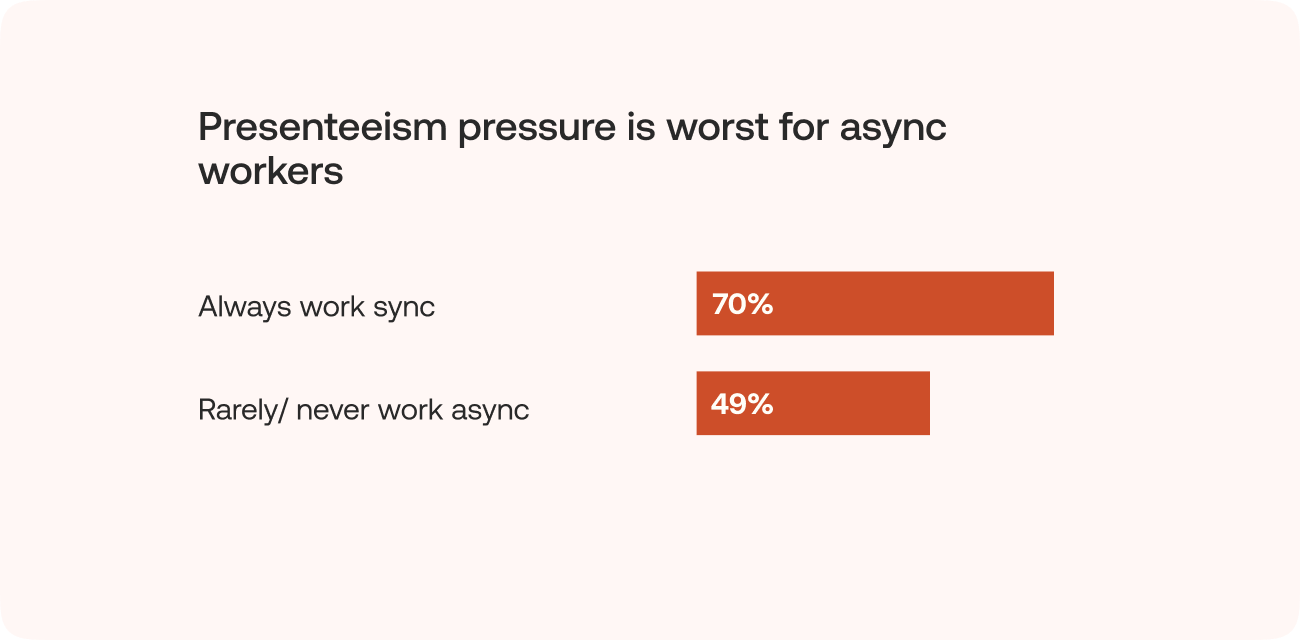

Of all those surveyed, 54% of people feel that there is pressure to be online at certain times of the day. But those who work asynchronously were actually more susceptible to presenteeism pressures. 70% of those surveyed said they experience pressure to be online and available more frequently than their at-work colleagues.

This demonstrates that even in organizations where async is possible and happening, workers still feel like they need to be online when their colleagues are. They worry that people won’t recognize they’re working, or understand the value they’re delivering, because it’s not visible. This is likely to be compounded by a concern that performance will be measured incorrectly too, and will negatively impact pay reviews and promotions. All this points to a much deeper cultural problem that still thinks of work in terms of a production line. ‘The longer people are sitting in front of a conveyor belt, the more widgets they can make’ - or so goes the logic. But the constraints of factory work just don’t apply to the knowledge work happening today.

How to stop the always-on culture

The good news is that there are lots of things you can do to make that cultural shift. To help, we’ve pulled together a short guide to help organizations make the transition. But let’s start with some of the basics.

First, you need to normalize asynchronous working. This is really about communication and talking about the way you work as a team or company. Leaders and managers need to make it clear that this is the way you expect work to be done and continue to reinforce this in all of your communication with your team, whether that’s All-Hands Meetings or 121s.

But talking alone will only get you so far. If employees still think they are being measured by other means, they will adapt their behavior accordingly. That’s why it’s critical that you change your recognition and reward structures, to make sure they are aligned with asynchronous working. Ultimately, this is about switching the emphasis from how many hours you work, to your output, and the value you create.

The way to do this is to make explicitly clear what is expected of people and what good results look like. If you get it right, the end result should be that everyone can focus on getting their work done, confident in the knowledge they will be assessed on the successful delivery of it, rather than how quick they have been to respond to messages at 8 pm in the evening.